The Psychology of Mediation, Part I: The Mediator’s Issues of Self and Identity

Originally published on mediate.com, this article discusses how mediators must deal with their own own egos while resolving conflicts.

It is an excerpted and edited version of relevant sections in Elizabeth Bader’s Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal article, published in 2010.

A version of the original article was also published in the International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies, an international peer-reviewed journal, in 2011.

On the basis of these articles, Elizabeth was awarded the Margaret S. Mahler Literature Prize in 2011.

Introduction

Issues of self-identity and self-esteem play an important role in negotiation and mediation. Sometimes they are spoken of in terms of a party’s need to “save face” or of a person’s “ego” clouding his thinking. They may also be referred to as “narcissistic issues,” a term that no longer necessarily connotes pathology. (1) Put simply, most people take the conflict personally and the outcome of the mediation as a reflection of who they are.

On a psychological level, parties in mediation typically move through a cycle of ego-inflation, deflation, and then, hopefully, realistic resolution. I call this the IDR cycle. (2) This process demands strength of self on a basic, simple, healthy ego level, especially at the outset. Parties strive to be equal to the task.

However, during impasse and other “critical moments,” (3) if the parties wish to reach resolution, they may have to release their psychological investments in the outcome of the negotiation. Thus, the capacity to let go is also a critical aspect of the psychology of mediation.

During critical moments, the mediator, too, may have to release the sense of narcissistic self-investment in the outcome. Thus, our usefulness as mediators will often depend on the extent to which we have learned to deal with issues of self and identity, not only in others, but in ourselves.

Psychoanalytic Theory on the Development of the Sense of Self and Identity

Psychoanalytic developmental theory consistently recognizes that with the development of a healthy sense of self, human beings also develop a reality-based and objective, but ideally also self-reflective, sense of self-and-other. This is what Peter Fonagy calls “reflective functioning.” (4) It is also, roughly, what Margaret Mahler calls “self and object constancy,” (5) and what intersubjective theorists describe as the capacity for mutual recognition, that is, the capacity for recognition, not just of one’s self, but of others. (6) This is especially important during conflict. Stated in practical terms, those who are able to function with adequate objectivity about themselves and others—or who can be encouraged to do so—will do better in mediation. (7)

Another significant theme is the importance of mirroring, the process in which one person reflects back to another, often by imitation or parallel conduct, the content of the other’s communication. Through mirroring and its intersubjective correlate, mutual recognition, (8) the self comes to know itself, and to relax in the secure awareness of its rightful place in the world.

“Looping,” (9) reframing and similar practices work well in mediation because they are actually a form of mirroring. They support the parties’ sense of self on a deep, if subtle level.

As Heinz Kohut and Ernest Wolf have observed, however, the degree of stability and coherence of the sense of self can differ widely in different people. (10) For example, while narcissists have a stable but grandiose sense of self, those with “identity diffusion” lack a clear sense of themselves and others. (11) One person may have a self strong enough to remain firm in the face of conflict, another may not. (12) Research in social psychology supports these observations, (13) and the finding that those with narcissistic tendencies are more likely to become aggressive in response to ego threat. (14)

The research on narcissism thus supports the view that much of the hostility and sense of insult parties exhibit in mediation is a defensive reaction to underlying feelings of shame or vulnerability.

Due to the primacy of issues of self and identity, the process of mediation is dominated, not just by narcissistic defenses such as grandiosity, but by reactions to those defensive or aggressive postures. For example, grandiosity or overconfidence will often be followed by disappointment and deflation. This causes the IDR cycle, which will be discussed in Part II of this article, soon to be published here.

Deeper Dimensions of the Self

In the mediation community we sometimes speak of the spiritual dimensions of conflict resolution. But what do we really mean by that? And does it have any practical importance in our lives and in our work?

Looked at from the perspective of issues of self and identity, we can see that the question of who we really are — and who the parties really are — is an implicit, profound issue in many mediations. It is an issue that has both spiritual and practical consequences.

For example, if one is working with a party who is feeling very vulnerable and offended by the way the other side is treating them, often the single most effective thing one can do is to communicate to the party — both verbally and most importantly nonverbally — that who they are is actually not contingent on the outcome of the mediation, or what others think. To hell with having one’s life ruled by the attitudes of the other side! It’s important to make decisions on the basis of what is good for you, not other people’s limited understanding or poor conduct.

Yet in order to communicate this effectively, one has to believe it oneself. Stated in practical terms, if you are working with someone whose identity is invested in whether they give or get $1,000,000 during a specific conflict, you will often be a lot more effective if you yourself do not believe that who they are is determined by their relationship to that particular pot of gold.

Working with the Mediator’s Own Issues of Self and Identity

The mediator’s ability to deal with issues of self and identity will thus often be a key ingredient of a successful mediation. But especially in tough cases, that can include our own issues. We are often not exempt from the underlying psychological dynamic in a mediation no matter how much we might wish it were otherwise.

In order to deal effectively with our own issues, it is best if we work on both a psychological level and a deeper level. On a psychological level, one should expect that one’s own issues of self and identity will arise to varying degrees during mediation. Knowledge of one’s relationship to narcissistic defenses, such as aggression, is important. It is also helpful to have a sense of the nature of one’s usual projections on others.

For example, self-observation may reveal one party has become an idealized version of one’s father, while another faintly echoes one’s mother, sister, or brother. There are countless possible permutations.

Understanding these projections will help to unpack one’s reactions and return to neutrality when parties become difficult or challenging. In many ways, this commitment to inner neutrality is an essential prerequisite to a truly well functioning outward neutrality. (15)

The Professional Ego Ideal

By analogy to the psychoanalytic literature on group therapy leadership, we also know that the “grandiose professional ego ideal” (16) is one of the key narcissistic dangers for the group leader. This grandiose self may desire to be seen as a “selfless helper.” (17) It may wish to be all powerful, all knowing and all loving as a defense to vulnerability. (18)

Paradoxically, the narcissistic leader in us may have the most difficulty tolerating the narcissism of clients, and may tend to devalue or avoid hearing them. (19) Classifying others as narcissistic may provide a way to project one’s own narcissistic tendencies onto others and to defensively disown them by doing so. (20)

Optimal functioning requires us instead to “accept that the grandiose ideal is an illusion and untenable . . . and to rebuild a more realistic professional ego ideal that accepts the limits of our power, knowledge, and love.” (21)

Ironically, when things become difficult during mediation, it may actually be one’s capacity to release a grandiose self-image that is of most service to the parties. (22) The hallmark of the competent mediator will be a realistic professional ideal, accompanied by a steady commitment to clients during the mediation. (23)

The Need for Kindness to Ourselves

It is also true, however, that as we go through the process of what is, essentially, the cultivation of humility, we must also cultivate the capacity to see ourselves without judgment and with compassion. In general, we need to learn to be as kind and understanding to ourselves as we would like to be or to have been to others. For many of us, this is a tall order. Yet it is necessary if we really want to be of service to others, and to stay committed to doing so over time.

Presence, Mindfulness, and Release of Identity

During mediation the parties experience the self of the mediator as her presence, on both a verbal and a nonverbal level. They continuously scan the mediator’s presence, assessing her strengths and weaknesses on a more or less continuous basis. (24)

This happens very quickly. According to Daniel Stern, It takes just one to ten seconds “to make meaningful groupings of stimuli emanating from people, to compose functional units of our behavior performances, and to permit consciousness to arise.” (25) Stern refers to this short “process unit” as the “present moment,” (26) or “the psychological present” (27) in therapy and in negotiation. (28) Viewed from this perspective, mediation is a fast-moving performance art, one that takes place within the rapidly unfolding present moments of the mediation. (29)

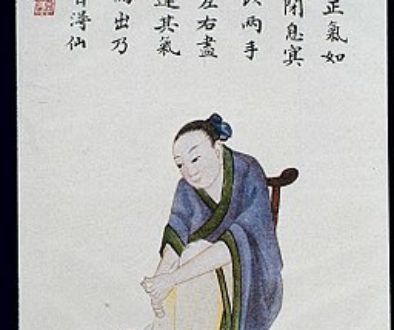

To help develop the capacity for moment-to-moment attunement, Professor Riskin and others have suggested that Buddhist mindfulness practice should be used by mediators, and included in the training curriculum. (30) In mindfulness practice, one remains “aware, moment to moment, without judgment, of one’s bodily sensations, thoughts, emotions, and consciousness.” (31) This disciplined form of reflective functioning (32) can help inhibit reactivity in situations of conflict. (33)

From the perspective of issues of self and identity, the great value of mindfulness practice, or other forms of meditation, (34) is that, as long as they are used judiciously and appropriately, (35) they can help release the usual sense of self-identity. (36) The transient nature of habitual thoughts and feelings becomes more evident when set against a backdrop of awareness. (37) Attitudinal and other biases also become more evident. This can help mediators maintain neutrality. (38)

In the ideal case, a sense of reverence and respect for one’s self and others is also developed through meditation and similar practices. In other words, one develops not only the capacity for mindful awareness but also the ability to reach into the moment of the mediation with a positive sense of affirmation.

To the extent this happens, parties will more readily experience the mediator’s presence as a source of support and objectivity. This is a positive aspect of what neuroscientists call the social brain. (39)

End Notes

1. For more on this point, see Elizabeth Bader, The Psychology of Mediation: Issues of Self and Identity and the IDR Cycle, 10 PEPP. DISP. RESOL. L. J. 183, n. 2 (2010). In brief, the term “narcissism” originally had an autoerotic, and therefore a pejorative, connotation. See, e.g., SIGMUND FREUD, On Narcissism: An Introduction, in THE STANDARD EDITION OF THE COMPLETE PSYCHOLOGICAL WORKS OF SIGMUND FREUD (James Strachey et al. trans., 1966), reprinted in ESSENTIAL PAPERS ON NARCISSISM 17 (Andrew P. Morrison ed., 1986). This is no longer the case. See Leonard Horwitz, Narcissistic Leadership in Psychotherapy Groups, 50 INT’L. J. GROUP PSYCHOTHERAPY 219-20 (2000) (explaining that, contrary to older views, narcissism is now considered to be “shared by all humans” and as “vital . . . as the physiological functions of temperature, respiration, and heartbeat.”).

2. The IDR cycle is also discussed extensively in Part IV of the Elizabeth Bader’s Pepperdine article. See Bader supra note 1, at 204-214 .

3. Critical moments are turning points in negotiations, the points at which meaning shifts. See, e.g., Lawrence Susskind, Ten Propositions Regarding Critical Moments in Negotiation, 20 NEGOT. J. 339, 339-340 (2004).

4. Psychoanalytic developmental theory is discussed at length in Part IA of Elizabeth Bader’s Pepperdine article. Bader, supra note 1, at 184-194. In particular, the work of Peter Fonagy and his colleagues is discussed at 191-192. On the work of Peter Fonagy generally, see PETER FONAGY ET AL., AFFECT REGULATION, MENTALIZATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE SELF 53-54 (2004).

5. JOYCE EDWARD ET AL., SEPARATION/INDIVIDUATION: THEORY AND APPLICATION 154 (2d ed. 1992) (“It is the achievement of self and object constancy over time that enables human beings to experience themselves as members of the family of humankind, and, at the same time, makes it possible for each of us to endure and adapt to the inevitable experiences of aloneness. . . .”). See also Bader, supra note 1, at 187-188, esp. notes 34-40 (discussing object constancy and the capacity to know oneself and others in self and object constancy). On Mahler’s work generally, see MARGARET S. MAHLER ET AL., THE PSYCHOLOGICAL BIRTH OF THE HUMAN INFANT, SYMBIOSIS AND INDIVIDUATION (1975). I am indebted to William Singletary for pointing out that there are similarities in the concepts of reflective functioning and self and object constancy. Communication with William Singletary (Dec. 2007). See also Gyorgy Gergely, Approaching Mahler: New Perspectives on Normal Autism, Symbiosis, Splitting and Libidinal Object Constancy from Cognitive Developmental Theory, 48 J. AM. PSYCHOANALYTIC ASS’N 1197, 1214-22 (2000) (integrating Mahler’s concept of object constancy with recent psychoanalytic theory, including the work of Fonagy).

6. For similar concepts in the work of Heinz Kohut and Otto Kernberg, see, e.g., HEINZ KOHUT, HOW DOES ANALYSIS CURE? 52, 70, 77, 79 (Arnold Goldberg & Paul E. Stepansky eds., 1984); see also Otto Kernberg, Identity: Recent Findings and Clinical Implications, LXXV Psychoanalytic Q. 969, 981 (2006) (emphasizing the importance of “the early capacity for differentiation between self and other”).

7. A similar point is made in two recent perceptive studies of mediation. See Kenneth Cloke, Mediation, Ego and I: Who, Exactly, Is In Conflict?, in HANDBOOK OF CONTEMPORARY PSYCHOTHERAPY: TOWARD AN IMPROVED UNDERSTANDING OF EFFECTIVE PSYCHOTHERAPY 127 (William O’Donohue & Steven R. Graybar eds., 2008) (drawing on the work of Sigmund and Anna Freud, among others, and noting “our purpose as mediators is . . . to develop [parties’] sense of self and other”). See also Richard McGuigan & Nancy Popp, The Self in Conflict: The Evolution of Mediation, 25 CONFLICT RESOL. Q. 221 (2007) (discussing the “authoring mindset,” which, as distinguished from the “affiliative” or “instrumental” mindsets, is more able to take into consideration the views of self and other. McGuigan and Popp rely on constructive developmental theory, id. at 223, as articulated in Robert Kegan’s work. See ROBERT KEGAN, THE EVOLVING SELF: PROBLEM & PROCESS IN HUMAN DEVELOPMENT (1982). Kegan sought to establish a tradition outside of classical psychoanalysis, based largely on the work of Jean Piaget, id. at 3-4, but which could be used to augment the work of various psychoanalytic theorists, including Mahler. Id. at 4. He argued his approach would be useful for therapists and counselors. But see K. Eriksen, The Constructive Developmental Theory of Robert Kegan, 14 FAM. J. 290 (2006) (arguing Kegan’s work has not received wide enough acceptance in the counseling community).

8. In childhood, mirroring includes the familiar type of activity where mother responds to her infant’s vocalizations by repeating them back, or where she responds to the infant’s activity by engaging in the same or similar activity. Margaret S. Mahler, THE SELECTED PAPERS OF MARGARET S. MAHLER, VOL. II, SEPARATION-INDIVIDUATION 86-87 (1979). On the distinctions between mirroring and recognition in psychoanalytic developmental theory see Stephen A. Mitchell, Juggling Paradoxes: Commentary on the Work of Jessica Benjamin, 1 STUDIES IN GENDER & SEXUALITY 251-55 (2000). Cf. Gergely, supra note 5, at 1206-10 (discussing points of similarity and difference in concepts of mirroring in Mahler and recent theorists).

9. Looping is the term used by Gary J. Friedman and Jack Himmelstein to describe the process of the mediator’s reciting back or neutrally paraphrasing the statements of parties or counsel in order to demonstrate understanding. Gary J. Friedman & Jack Himmelstein, Resolving Conflict Together: The Understanding-Based Model of Mediation, 2006 J. DISP. RESOL. 523, 529-537 (2006) (discussing and demonstrating practice of looping). See also GARY J. FRIEDMAN & JACK HIMMELSTEIN, CHALLENGING CONFLICT: MEDIATING THROUGH UNDERSTANDING 68-76 (2008) (discussing theory more extensively). For a philosopher’s view of this practice, see JACOB NEEDLEMAN, WHY CAN’T WE BE GOOD? 58-81 (2007) (demonstrating and discussing the same practice, although without using the term “looping”).

10. Heinz Kohut & Ernest Wolf, The Disorders of the Self and Their Treatment: An Outline, 59 INT’L J. PSYCHOANALYSIS 414 (1978), reprinted in ESSENTIAL PAPERS, supra note 2, at 175, 177 (“The adult self may . . . exist in states of varying degrees of coherence, from cohesion to fragmentation; in states of varying degrees of vitality, from vigor to enfeeblement; in states of varying degrees of functional harmony, from order to chaos.”).

11 . Otto Kernberg, Identity: Recent Findings and Clinical Implications, LXXV Psychoanalytic Q. 969, 988 (2006) (arguing that borderlines typify the syndrome of identity diffusion, which is characterized by a lack of integration of the concept of self and others; but “in the case of narcissistic personality disorder, what is most characteristic is the presence of an apparently integrated but pathological, grandiose self, contrasting sharply with a severe incapacity to develop an integrated view of significant others.”).

12. Kohut & Wolf, supra note 10, at 414 (noting that a strong self allows us to tolerate victory or defeat, success or failure).

13. See Brad J. Bushman & Roy F. Baumeister, Threatened Egotism, Narcissism and Self-Esteem and Direct and Displaced Aggression: Does Self-Love or Self-Hate Lead to Violence?, 75 J. PERS. & SOC. PSYCHOL. 219, 227-28 (1998) (“High self-esteem . . . may be stable and largely impervious to evaluations by others, or it may demand frequent confirmation and validation by others and be prone to fluctuate in response to daily events”); Christine H. Jordan et al., Secure and Defensive High Self-Esteem, 85 J. PERS. & SOC. PSYCHOL. 969, 975 (2003) (noting that high self-esteem “ . . . can assume relatively secure or defensive forms that relate to whether an individual possesses less conscious, negative self-feelings”); T. S. Stucke & S. L. Sporer, When a Grandiose Self-Image Is Threatened: Narcissism and Self-Concept Clarity as Predictors of Negative Emotions and Aggression Following Ego-Threat, 70 J. PERSONALITY 509, 530 (2002) (“our findings can be seen as additional evidence for the notion that individuals with a positive but unstable and insecure self-view are especially vulnerable to ego-threats.”).

14. Bushman & Baumeister, supra note 13, at 227; see also Tanja S. Stucke, Who’s to Blame? Narcissism and Self-Serving Attributions Following Feedback, 17 EUR. J. PERSONALITY 465, 466 (2003) (“after negative feedback narcissistic individuals are prone to negative reactions directed toward others”).

15. See also infra note 38 (discussing neutrality).

16. Robert L. Weber & Jerome S. Gans, The Group Therapist’s Shame: A Much Undiscussed Topic, 53 INT’L. J. GROUP PSYCHOTHERAPY 395, 399 (2003).

17. Horwitz, supra note 1, at 222.

18. Weber & Gans, supra note 10, at 399.

19. Horwitz, supra note 1, at 231-32.

20. Id. at 233.

21 . Weber & Gans, supra note 10, at 414.

22. This is discussed further in the Part IV of Elizabeth Bader’s Pepperdine article. Bader, supra note 1, at 204 -214.

23. Cf. Horowitz, supra note 1, at 223-24 (noting effective therapists seek to maintain a steady commitment to clients not their own gratification or an unrealistic sense of their own prowess).

24. Sarah-Jayne Blakemore & Jean Decety, From the Perception of Action to the Understanding of Intention, 2 NATURE REVIEWS NEUROSCIENCE 561, 563-65 (2001) (“The medial prefrontal cortex is consistently activated by . . . tasks in which subjects think about their own or others’ mental states.”); DANIEL STERN, THE PRESENT MOMENT IN PSYCHOTHERAPY AND EVERYDAY LIFE 79 (2004) (explaining that the visual information we receive when we watch another gets mapped onto equivalent motor representations in our own brain by the activity of the mirror neurons).

25. Id. at 41.

26. Id.

27. Id. at 50.

28. Stern drew an analogy between “present moment(s)” in therapy and negotiation in an article he published in an edition of the Negotiation Journal devoted to critical moments in negotiation. Daniel N. Stern, The Present Moment as a Critical Moment, 20 NEGOT. J. 365 (2004). I assume the analogy also extends to mediation.

29. See Carrie Menkel-Meadow, Critical Moments in Negotiation: Implications for Research, Pedagogy, and Practice, 20 NEGOT. J. 341, 346-47 (2004) (“Our practice as negotiators and mediators draws from many fields of insights and virtuosity. We seem to be adding an explicit focus on the performance arts as well, for we are indeed ‘performers’ too.”). See also Susskind, supra note 3, at 339-40 (likening skills in negotiation to jazz improvisation and acting skills).

30. Leonard L. Riskin, Mindfulness: Foundational Training for Dispute Resolution, 54 J. LEGAL EDUC. 79, 86-88 (2004). Buddhism has had a profound impact on mediation. For example, in recent years Zen Buddhist priest and author Norman Fischer has participated as a trainer in mediation training programs held at the Center for Mediation in Law with Gary J. Friedman and Jack Himmelstein. A forum at Harvard and part of an issue of the Harvard Negotiation Law Review were devoted to mindfulness. See Symposium, Mindfulness in the Law and ADR, 7 HARV. NEGOT. L. REV. 1 (2002).

31. Riskin, supra note 30, at 83; see also Leonard L. Riskin, The Contemplative Lawyer: On the Potential Contributions of Mindfulness Meditation to Law Students, Lawyers, and Their Clients, 7 HARV. NEGOT. L. REV. 1 (2002).

32. DANIEL J. SIEGEL, MINDFUL BRAIN: REFLECTION AND ATTUNEMENT IN THE CULTIVATION OF WELL-BEING 205 (2007) (drawing an analogy between mindfulness and reflective functioning in secure attachment and citing Peter Fonagy & Mary Target, Attachment and Reflective Function: Their Role in Self-Organization, 9 DEV. & PSYCHOPATHOLOGY 679 (1997)).

33. Kirk Warren Brown et al., Mindfulness: Theoretical Foundations and Evidence for Its Salutary Effects, 18 PSYCHOL. INQUIRY 211, 225 (2007) (reviewing research).

34. See DANIEL GOLEMAN, THE MEDITATIVE MIND: THE VARIETIES OF THE MEDITATIVE EXPERIENCE (1977) (discussing a variety of meditation practices, Eastern and Western, although the perspective is largely Buddhist).

35. On some of the dangers to the self that may attend the inappropriate use of spiritual practice, and particularly the dangers of self-deception in groups, see Frances Vaughan, A Question of Balance: Health and Pathology in New Religious Movements, in SPIRITUAL CHOICES 265, 272-73 (Dick Anthony et al. eds., 1987).

36. See Brown et al., supra note 33, at 216 (in mindfulness, there is an “introduction of a mental gap between attention and its objects, including self-relevant contents of consciousness. This de-coupling of consciousness and mental content . . . means that self-regulation is more clearly driven by awareness itself, rather than by self-relevant cognition.”).

37. MARK EPSTEIN, PSYCHOTHERAPY WITHOUT THE SELF: A BUDDHIST PERSPECTIVE 48-52 (2007); CLAUDIO NARANJO & ROBERT E. ORNSTEIN, ON THE PSYCHOLOGY OF MEDITATION 86-87 (1971) (discussing this aspect of mindfulness meditation).

38. “Mindfulness, cultivated through meditation allows a mediator to approach neutrality in discourse through a strengthened ability to recognize personal bias when it occurs and reduce the influence of such bias on his speech and actions.” Evan M. Rock, Note, Mindfulness Meditation, The Cultivation of Awareness, Mediator Neutrality, and the Possibility of Justice, 6 CARDOZO J. CONFLICT RESOL. 347, 363 (2005). See also Darshan Brach, A Logic for the Magic of Mindful Negotiation, 24 NEGOT. J. 25, 30 (2008) (discussing the usefulness of the mindful negotiator taking the observer’s perspective during negotiation).

39. The social brain is also discussed extensively in Part II.A of the Pepperdine article. See Bader supra note 1, at 198; see also DANIEL GOLEMAN, SOCIAL INTELLIGENCE, THE NEW SCIENCE OF HUMAN RELATIONSHIPS 43 (2006) (discussing the motor neurons: “This triggering of parallel circuitry in two brains lets us instantly achieve a shared sense of what counts in a given moment . . . . Neuroscientists call that mutually reverberating state ‘empathic resonance,’ a brain-to-brain linkage . . . .”).